Ludmila Mlynarova was born in 1946. She originally comes from Mladejovice u Sternberka. Her father was a musician. He led choirs, taught music education and played an organ at a church. He also had a few musical bands. Her mother was ill incessantly and thus unemployed.

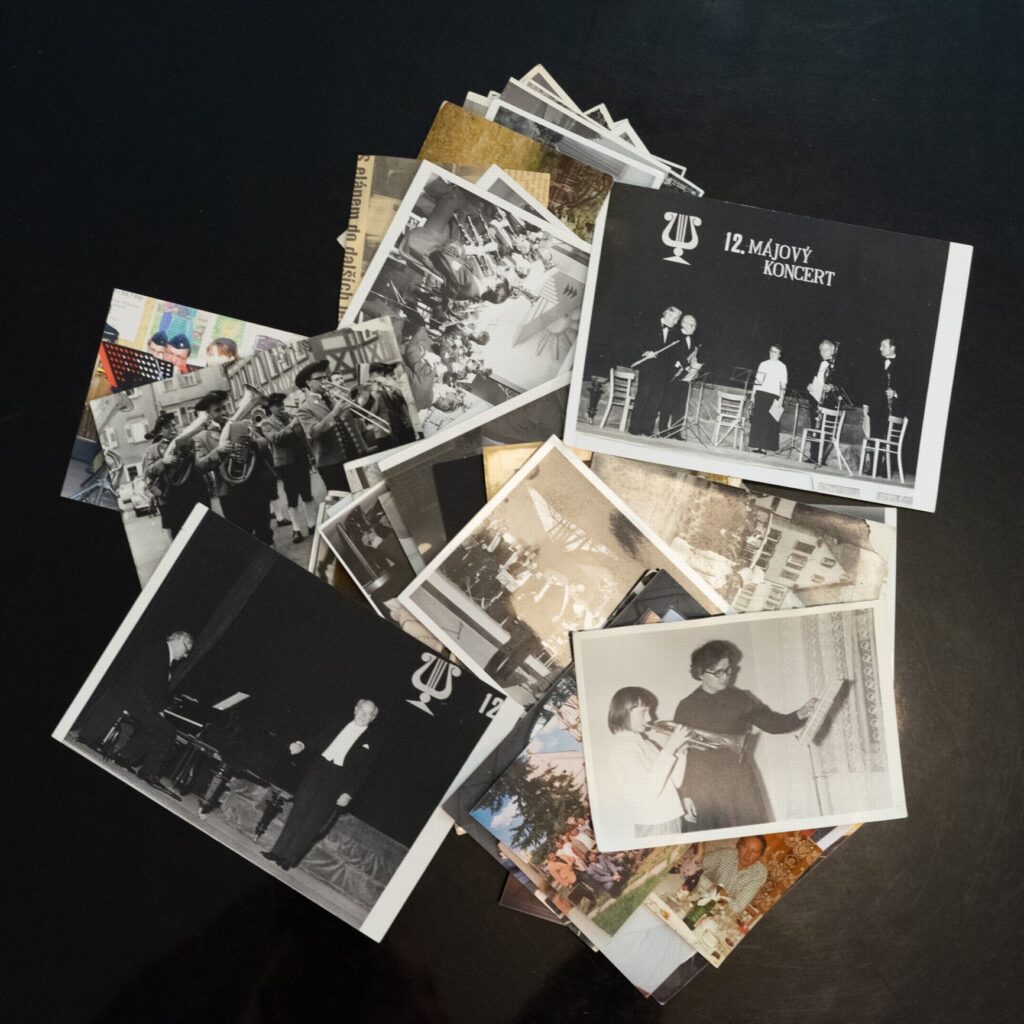

She had 6 siblings. After finishing primary school, she worked as a labourer at Zora (a confection and chocolate factory). Afterwards she taught music classes in Moravsky Beroun while she studied conservatoire in Brno. Her main musical instrument is a French horn. After graduating at the conservatoire, she played the French horn at Moravske divadlo (Moravian theatre) in Olomouc for 30 years.

She travelled abroad to play during the socialism. She was in Hong Kong and West Germany. She and her colleagues got assigned special overseers who checked if they didn’t deflect from socialistic ideals.

Immerse in the life story of Mrs Ludmila Mlynarova below.

She spent one year at children’s home

There was a shortage of food after the 2nd World War. The food was given to people in exchange for food stamps. The food stamps were given to the people in sets. One set per person. There were 9 of them in the family. Her mother and father, she and 6 siblings. They got only one set from the communistic regime. It meant they didn’t have enough to eat. It forced her parents to move her and her siblings to a children’s home for a year.

She says about the stay: “The worst thing was that there were two types of children’s home. The first one was for children up to the age of 6 and the second one which was for children above that age. I went to the first one. The rest of my siblings went to the second one. They separated us. It was unpleasant. On the other hand, I can’t complain about anything else.”

The children’s home was situated in Oskava. In the end, she doesn’t remember it exactly, they were given the food stamps and could return home.

Black sheep at school

They were considered black sheep at primary school. Her father was considered inconvenient by the communistic regime. I asked her why they didn’t like him and she replied: “He played the organ and led a choir at the church. He didn’t jump through hoops as they expected him to. He didn’t praise them. People hurt each other all the time. However, nobody could talk about it at that time.”

Thus they were given very bad grades at primary school. She got Es and Fs and her sister got a bad grade from behaviour. Ludmila even got F from music education.

It changed when they moved to lower secondary school (ISCED 2). There was a different director. Their grades changed to As and Bs immediately.

Ludmila thinks that the inconvenience of her father caused their departure to the children’s home. It means that they weren’t given the food stamps in 1952 by the communists on purpose so as to punish her family. Her farther was labelled as “lazy” by the regime.

She learnt multiple musical instruments just to teach them

After finishing primary and lower secondary school (ISCED 1 and 2), she worked as a labourer at Zora and babysat small children. Afterwards she taught music and how to play musical instruments for 10 years in Moravsky Beroun and studied at the same time at musical conservatoire in Brno. The studies took 6 years. It was four years until receiving a school-leaving exam (ISCED 3) and an additional two-year period of learning how to play a musical instrument. Her main musical instrument was the French horn. After the graduation she visited and learnt from her French horn teacher for another 2 years privately.

She liked Brno. She also liked that the teachers of the conservatoire came from a professional background. They played in orchestras theatres and so on. They were experienced.

She can also play a violin perfectly. She learnt more instruments as: a guitar, a violoncello, an accordion, a trumpet etc. in order to teach them. She comments: “There was always somebody coming over to me and telling me: ‘I want to play this and that musical instrument please,’ so I learnt them in order to teach them. After a while my students were better at playing them than I was.”

Moravian theatre was refuge for subversive elements

After graduating from the conservatoire, she got a job in an orchestra of Moravian theatre (Moravske divadlo) in Olomouc. They played in Olomouc where the theatre is located as well as in: Gottwaldov (Zlin), Opava, Unicov. She also went abroad during the communism. She was in Poland, France, West Germany and Hong Kong. The only place she didn’t visit was Russia, which made her laugh.

The orchestra served as a musical background for an opera or an operetta. The operetta had been located in Hodolany (a city district of Olomouc) but was joined with the Moravian theatre later.

I asked her who was in the audience visiting the opera because I consider the opera to be for high society. Ludmila Mlynarova says: “I would say that normal people went to see it. We even played České jesličky (A Czech biblical opera). We performed it for two years. Many nuns attended it. It was very interesting – black and white.”

When she was accepted to the theatre, a special communistic ideological report on employees (kadrovy posudek) wasn’t as important as with other employers.

* kadrovy posudek (a special communistic ideological report on employees) = It was a type of a personal report of employees effective from 1948 till 1989. The result of the report was important for being accepted or not being accepted to a job. The main criterion for a good report were a social class (ideally a manual labourer), opinions of the employee and an ideological attitude towards the communistic regime. It was promoting based on absolutely the opposite of merit and abilities (meritocracy).

The kadrovy posudek and surrounding things weren’t taken so seriously at the Moravian theatre. It was rather a refugee for people who were inconvenient for the regime. She knows about a case of a person who wanted to become a priest. He didn’t manage to get accepted at the university. People interested in the religion were a thorn in the regime’s side. He wasn’t accepted to any other university and ended up as a stagehand at the theatre. Ludmila Mlynarova says: “Many people went to work to the theatre because their attitude towards the regime wasn’t so important there.”

There was a special communistic ideological reports on employees department in the theatre as in any other national companies (a private company and private entrepreneurship didn’t exist during the socialism). The name in Czech language is “kadrove oddeleni”. The name of a person working in the department was “kadrovy pracovnik”. The purpose of kadrovy pracovnik was to create the reports and recommend employees for a promotion and hiring. Their kadrovy pracovnik was a very good musician who had an understanding for everything. Thus they didn’t have any problems with him. She adds: “If a person had a bad ideological report, they got hired at the theatre.”

After the Velvet revolution in 1989, the kadrove oddeleni were renamed to personnel departments (human resources departments).

In Hong Kong and West Germany with overseers

When they went abroad with the orchestra, specially designated overseers were sent with them. Four to seven of them were sent and each group of musicians had one of them assigned. The overseers checked if they didn’t deviate from socialistic ideals.

When they were abroad, they didn’t have much free time, they performed all the time. Musicians didn’t care about the politics much. She met colleagues from all around the world. For example: Americans, Australians, Asians and the blacks. They all had a concert together at the end of the stay.

There was a shortage of foreign currencies during the communism. They were rationed to people travelling abroad. Mrs Mlynarova didn’t see it as a problem. They stayed accommodated at the same family four times in Menningen in the West Germany. They were great musicians. They took care of them and didn’t mind to buy something for them or give them stuff for free.

I asked her which language they used to talk to each other. She answered: “Musicians don’t need to talk, the music speaks for them. We took out a score/sheet music and played.”

Havel ist eins

She went to Germany a short time after the Velvet revolution and met with a random German, also a musician. He said: “Havel ist eins,” with a thumbs-up. She was pleased. She adds: “It pleased me at that time. I was proud of my Czech heritage.”

They still remember me

She has come across her former student from Moravsky Beroun recently. She taught her.

Me: “Did you like that somebody still remembers you?”

Ludmila Mlynarova: “Yes of course! They even invited me to Moravsky Beroun. Perhaps there will be a celebrations of the anniversary of the musical school. I am going to go there.”

Conclusion

What about you? Do you know anybody who has something to share? Comment below or write me a message.